Sexual anatomy typically refers to the both the external sexual organs, like the vulva and penis, and the internal organs involved in reproduction, like the uterus and seminal vesicle. We categorize this anatomy as either female or male, but not necessarily the person. A person’s anatomy doesn’t determine their gender.

Based on sexual anatomy, a person is typically assigned a sex at birth—female or male. Sometimes a person’s sexual anatomy isn’t characteristically male or female, though—what is called intersex. Intersex is an umbrella term for differences in sex traits or reproductive anatomy. Intersex people are born with these differences or develop them in childhood. There are many possible differences in genitalia, hormones, internal anatomy, or chromosomes. People who are intersex have reproductive traits or sexual anatomy that does not conform to the sex binary of male or female.

Gender is shaped by social and cultural norms and expectations of behavior. A person’s gender identity—their own personal perception of themselves—as female, male, both, or neither—does not necessarily match their biological sex. A person expresses their gender in various ways, such as their name, pronouns, dress, hairstyle, and more. Some gender terms that are important to know include:

- Cisgender refers to a person whose gender identity matches the sex they were assigned at birth.

- Transgender refers to a person whose gender identity does not match the sex they were assigned at birth. For example, a person who was assigned female at birth but identifies as male may be called a transman.

- Nonbinary refers to a person who may identify as male and female, neither, or somewhere between. Some, but not all, nonbinary people consider themselves transgender because they don’t identify with the sex they were assigned at birth.

When we talk about sexual anatomy here, we talk about it in a binary way—male and female. But we are talking about biological sex, not gender identity or expression. So let’s learn about this part of the body and how it works.

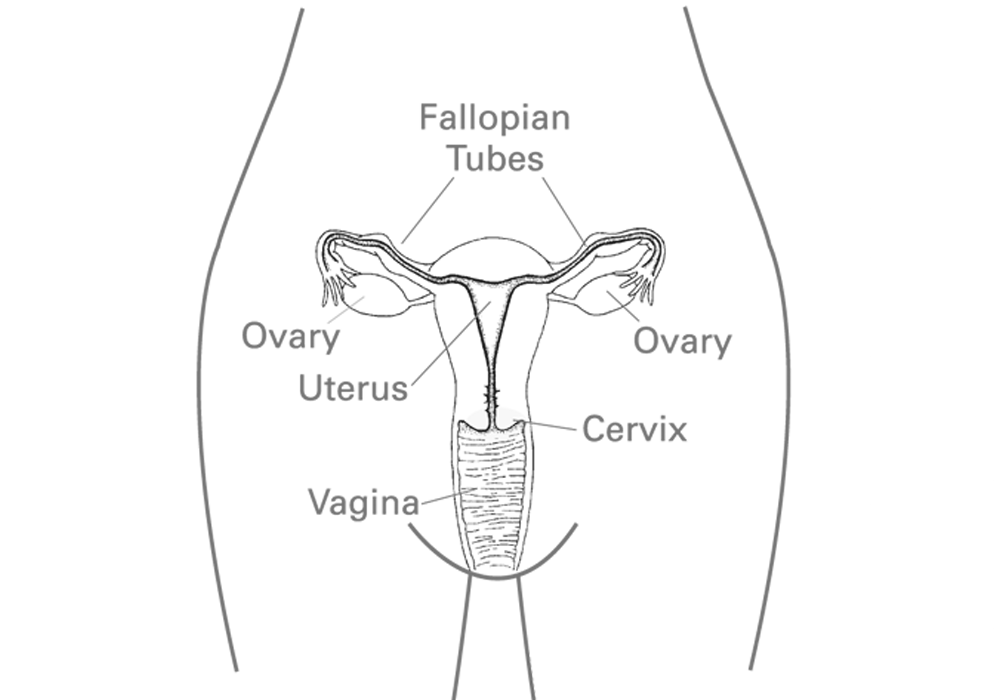

Female Reproductive System

The female reproductive system includes the ovaries, the uterus, fallopian tubes, the cervix, and the vagina. Click on the buttons below to learn more about each.

These are narrow tubes that are attached to the upper part of the uterus and serve as tunnels for the ova (egg cells) to travel from the ovaries to the uterus.

Starting at puberty, the ovaries begin to release eggs regularly. The eggs travel from the fallopian tubes into the uterus and eventually are flushed out of the body, along with uterine lining, through the vagina. This process is called the menstrual cycle. A regular cycle averages about 28 days, but it can range from 21-45 days.

If an egg is fertilized by sperm in a fallopian tube, that fertilized egg will typically travel to the uterus. Once there, that egg may or may not implant in the walls of the uterus and continue to grow—resulting in pregnancy. Sometimes, the fertilized egg doesn’t implant and is flushed out during menstruation (a.k.a period).

Sometimes, the fertilized egg implants in the fallopian tube. This is called an ectopic pregnancy and requires treatment immediately. The fertilized egg can’t survive here and if continued to grow, it can cause the tube to rupture and cause life-threatening bleeding.

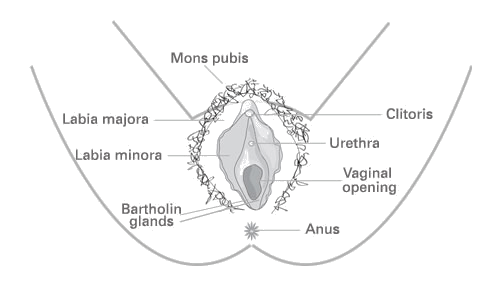

Now let’s take a look at the external sexual anatomy:

The mons pubis is the rounded fatty mass over the pubic bone covered with hair and coarse skin. It acts as a buffer during sexual intercourse, preventing injury to the underlying bone. It also contains sebaceous and sweat glands. Some of the latter form a specialized type of gland called the apocrine glands. These glands release a secretion with a characteristic smell that increases sexual attraction.

The above drawing is just a basic idea of the external female genitalia—it is an example, not the standard. In fact, there is no standard. The appearance of genitals vary a great deal from person to person. Labia minora may be longer than the outer labia. The color of labia may change as you age. Clitorises vary in size, shape, and location. Your vulva is beautiful and uniquely yours.

If you’d like to get an idea of just how much all of this varies, you can take a look at The Labia Gallery from Women’s Health Victoria. The models in the gallery reflect a wide range of ages and genders and show just how diverse external genitalia really is. You can also check out vulva portraits and personal stories at The Vulva Gallery, a project of Amsterdam-based illustrator Hilde Atalanta. This collection of vulva portraits showcases a wide variety of vulvas alongside personal stories celebrating body diversity.

We’re all different, so there is no “normal” when it comes to genital appearance. The same goes for male genital anatomy. Let’s take a look:

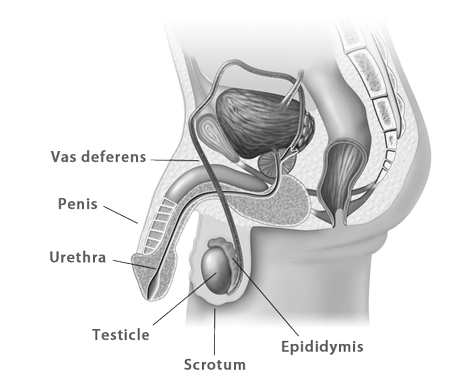

Male Sexual Anatomy

The penis is the most visible part of the male sexual anatomy. It is made up of two parts, the shaft and the glans (also called the head). The shaft houses the corpora cavernosa (two flexible cylinders comprised of erectile tissue that run the length of the penis and support erections), and the corpus spongiosum (erectile tissue surrounding the urethra). During orgasm, a thick fluid (semen) is released through the urethral opening at the tip of the penis. Urine also leaves the body through the urethral opening.

As for the penis, much of the concern revolves around size. Penis size is determined entirely by factors out of our control. But questions about size abound; What’s the average penis size? Can I increase my penis size? Does it matter as much as I think it does?

The answer to the last one is easy—no, it doesn’t. A review of various studies showed that the average size for a flaccid (non-erect) penis is 3.61 inches, and 5.16 inches for an erect penis. But average does not mean normal. Just as with vulvas, there is no one normal. Instead there is just beauty in diversity. You can see some of this in the work of photographer Laura Dodsworth, who shares portraits of 100 men in her book Manhood: The Bare Reality. Both cisgender and transgender men share their stories—and photos of their penises—in another celebration of genital diversity.

Getting Care

It’s important to know how your body works, and be able to recognize when something isn’t quite right. If something changes or doesn’t seem quite right, get checked by a health care provider. But also know that there are recommendations for regular sexual health care.